The rapid rise of artificial intelligence is fueling unprecedented demand for data centers vast facilities that process and store the world’s digital information.

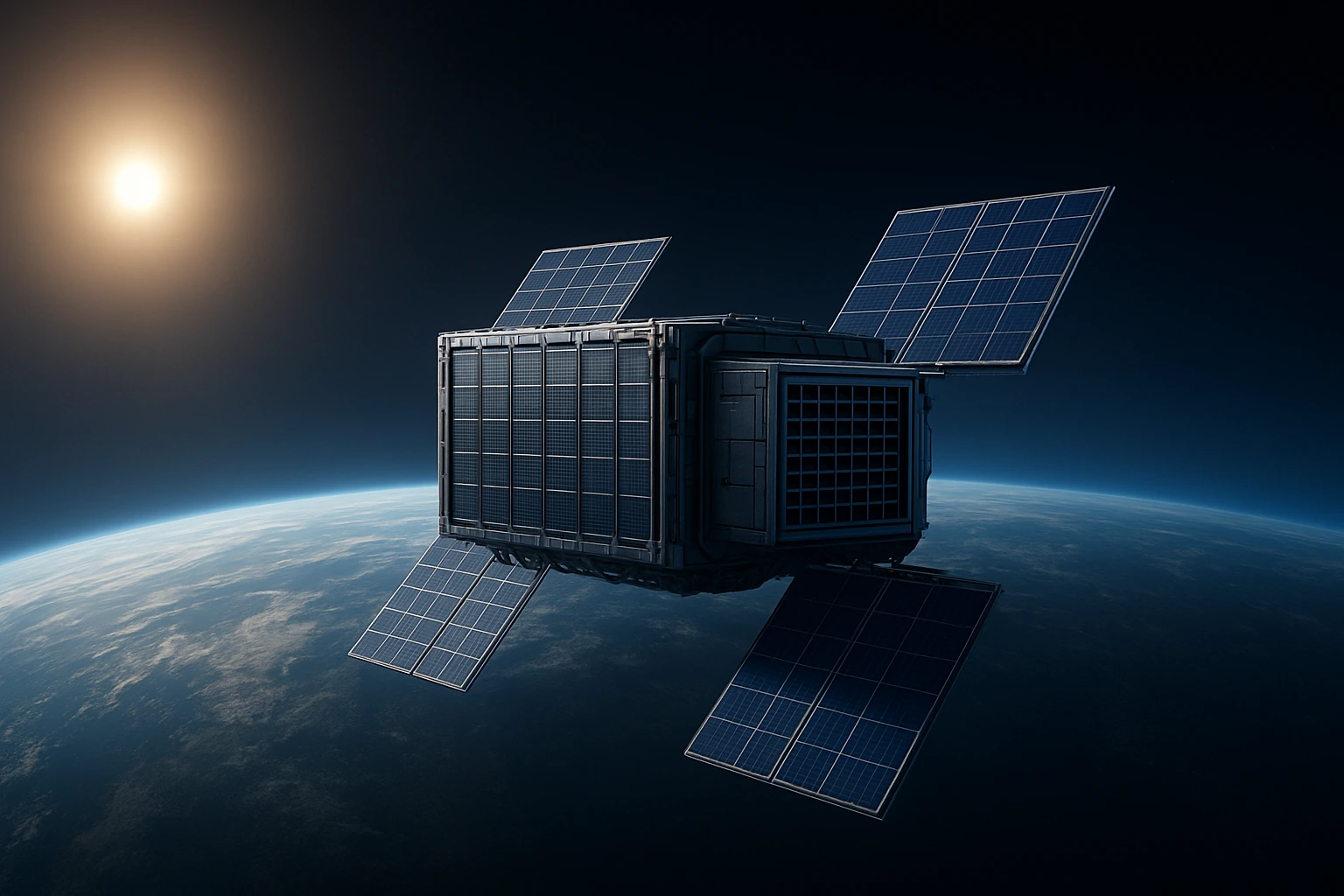

But as these centers multiply across the globe, their growing appetite for electricity and land is creating new environmental and logistical challenges. Now, several organizations are looking skyward for a solution building data centers in space.

The idea, once confined to science fiction, is being tested by government backed research projects and startups that believe orbiting data infrastructure could reduce Earth’s carbon footprint while offering continuous access to solar power.

According to a 2024 report from Goldman Sachs, global data center power demand is projected to rise by 165 percent by 2030. Data centers already account for about 2 percent of global electricity consumption and are responsible for significant carbon dioxide emissions.

Although many facilities are turning to renewable energy, large-scale solar and wind farms require extensive land use an increasingly scarce resource near major cities and tech hubs.

To address this dilemma, the European Commission launched the ASCEND Project, led by France based Thales Alenia Space, to assess the feasibility of deploying data centers in orbit.

By harnessing uninterrupted solar energy beyond Earth’s atmosphere, proponents argue that such systems could operate with minimal environmental impact.

“Space offers unique conditions for energy efficiency,” said Xavier Roser, a systems engineer at Thales Alenia Space. “In orbit, there’s no night, no weather, and no atmospheric interference making it possible to generate and use solar energy continuously.”

However, Roser cautioned that major technological and economic challenges remain before the concept can move beyond the experimental phase.

Experts say the environmental benefits of space based data centers depend largely on advancements in rocket technology and materials science.

Launching heavy infrastructure into orbit remains carbon intensive, offsetting much of the potential gain from clean space energy. “The emissions from rocket launches are still small compared to aviation.

But they occur at higher altitudes where pollutants linger longer,” said Dr. Lena Hoffmann, an environmental physicist at the University of Munich. “To make this viable, rockets must become significantly cleaner and more reusable.”

The ASCEND study found that rockets would need to emit ten times less carbon over their lifecycle than current models to make orbital data centers environmentally advantageous.

So far, no company has announced a rocket design that meets that standard. SpaceX, which revolutionized launch economics with its reusable Falcon rockets, has not revealed plans for a “green” rocket.

However, industry analysts say the company’s ongoing development of methane fueled Starship vehicles could eventually reduce emissions per launch.

Data centers on Earth consume vast amounts of energy primarily for cooling. A 2023 report by the International Energy Agency estimated that cooling systems account for up to 40 percent of total power use in large data facilities.

Space based systems could potentially eliminate this need by using radiative cooling in the vacuum of space. Yet the cost remains prohibitive.

Current estimates suggest launching even a small scale orbital data module could cost hundreds of millions of dollars. By comparison, terrestrial facilities can be built for a fraction of that amount, even when powered by renewable energy.

Despite the challenges, investors and engineers argue that the long term savings in operational costs, coupled with near constant solar availability, could offset high launch expenses within a few decades.

In Abu Dhabi, Madari Space, a startup founded by pilot and engineer Shareef Al Romaithi, is among the pioneers testing this concept.

Partnering with Thales Alenia Space, Madari is preparing a 2026 mission to send a toaster sized payload containing data storage and processing components into orbit.

“Our goal is to build a constellation of data satellites capable of processing information in real time,” Al Romaithi said. “For Earth observation and defense applications, even a few seconds of faster data delivery can make a critical difference.”

He added that keeping sensitive data in orbit could also appeal to governments and corporations concerned about sovereignty and cybersecurity. “When your data is not bound to a single territory, you reduce certain geopolitical risks,” he said.

China has already entered the race. In May, the country launched twelve satellites for a planned 2,800 satellite space computing network, marking the first large-scale attempt to process data off-planet.

While the vision of orbiting data centers remains years perhaps decades away from reality, both public and private entities are investing in early stage research.

The European Union continues to fund feasibility studies under its Green Digital Infrastructure initiative, while private capital flows toward startups exploring in orbit manufacturing and modular computing architectures.

“Every disruptive technology starts as an expensive prototype,” said Dr. Karen Mitchell, a technology policy analyst at King’s College London.

“If launch costs keep falling and environmental regulations tighten, space based data processing could shift from a novelty to a necessity.”

Still, the environmental calculus remains uncertain. The production, launch, and eventual decommissioning of space based hardware could generate new waste and emissions if not carefully managed.

The race to build space based data centers underscores a broader global struggle: how to balance the world’s growing digital appetite with the planet’s finite resources.

For now, the concept represents both ambition and caution an audacious attempt to take one of Earth’s most energy hungry industries beyond the atmosphere.

Whether orbiting data centers become a practical solution or remain an engineering dream will depend on breakthroughs in propulsion, materials, and cost efficiency.

But as artificial intelligence drives data needs sky high, it may only be a matter of time before humanity’s digital cloud truly leaves Earth.